Maximizing the Power of Early Ed: The New TED Talk from FPG's Kate Gallagher

Assembly of the Healthy Child: The Right Next Steps

Assembly of the Healthy Child: The Right Next Steps

After FPG scientist Kathleen "Kate" Gallagher delivered her first TED Talk on the power of high-quality early education, it quickly became UNC's most popular of the year. This summer, she delivered the sequel at the TEDxMemphis conference, and now you can watch it here. Update: Both talks now are the most watched videos from their TEDx events.

In her new TED Talk, Assembly of the Healthy Child: The Right Next Steps, Gallagher explains how the most famous study on early education and care, FPG's Abecedarian Project, touched her own career, and in this clip she also explains how the study found remarkable lifetime benefits for high-quality early education.

Gallagher also covers more new ground, including this clip about the achievement gap and what some states and communities today are doing to address it.

She then turns to why high-quality early education holds such power for its recipients. The secret, she says, is in the development of early, meaningful, healthy relationships.

And who benefits? Gallagher says we all do. She cites research from Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman on the striking financial return on investment on high-quality early education programs. In addition, she discusses how economist Timothy Bartik's research shows that a commitment to early education can lift an entire community and has the potential to end the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

Gallagher concludes by suggesting that vibrant communities, and democracy itself, depend on contributions from as many informed, able-bodied participants as possible--and that these are the healthy community members that high-quality early education is helping to assemble.

The full-text of the new TEDxMemphis talk:

The full-text of the new TEDxMemphis talk:

I am here today as an educational psychologist, as a teacher and researcher. I’ve spent many years developing and learning about relationships with young children, their families, and the professionals who work with them. Today I’d like to share with you some of the things I have learned.

In the early 1980’s, while still a college student, I worked as a teacher assistant in a early intervention program designed to support toddlers who were considered at risk. Many children had delays or disabilities. Most were living in families who were struggling to care for them--families sometimes troubled by addiction, trauma, mental illness and, almost always, poverty. As a new teacher, I worked with a talented mentor teacher, who guided my work with each of the children. Toward the end of my first week, she gave me homework. "Kate, I would like you to go home tonight and choose two activities to do with Marcus to help him learn how to follow directions." And she handed me a little paperback called Learning Games. It consisted of playful activities, using language intensive 1:1 interactions between adults and children. I chose two activities, returned the next day, and played Learning Games with Marcus.

I’ve never done anything more important than helping Marcus learn to follow directions. Over the course of that year, we made a difference with him and his family. Little did I know then, but the Learning Games I was using with Marcus were the essential curriculum of the famous Abecedarian study from the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute. That’s A-be-ce-da-ri-an, which means “one who is just learning”--a perfect way to describe the young protagonists in a story that has been told mostly in research studies. It is a chapter of a larger story about the imperative for community investment in high-quality early childhood programs.

I’ve never done anything more important than helping Marcus learn to follow directions. Over the course of that year, we made a difference with him and his family. Little did I know then, but the Learning Games I was using with Marcus were the essential curriculum of the famous Abecedarian study from the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute. That’s A-be-ce-da-ri-an, which means “one who is just learning”--a perfect way to describe the young protagonists in a story that has been told mostly in research studies. It is a chapter of a larger story about the imperative for community investment in high-quality early childhood programs.

The Abecedarian study began with 100 North Carolina babies born into poverty. Children and their families were randomly assigned to either a group that received no intervention, or to the Abecedarian group, who received year-round, full-time educational childcare that emphasized 1:1 adult-child interactions, from infancy until age 5.

The researchers who developed the Learning Games curriculum expected to see rapid improvements in children’s intelligence, but they didn’t. The children were toddlers before the differences between the groups of children were apparent. From there the differences grew. And the children who experienced full day, language- and interaction-rich Abecedarian childcare continue to demonstrate benefits that have lasted a lifetime.

In middle and high school, the Abecedarians outperformed their non-participating peers on intelligence, reading and math assessments.

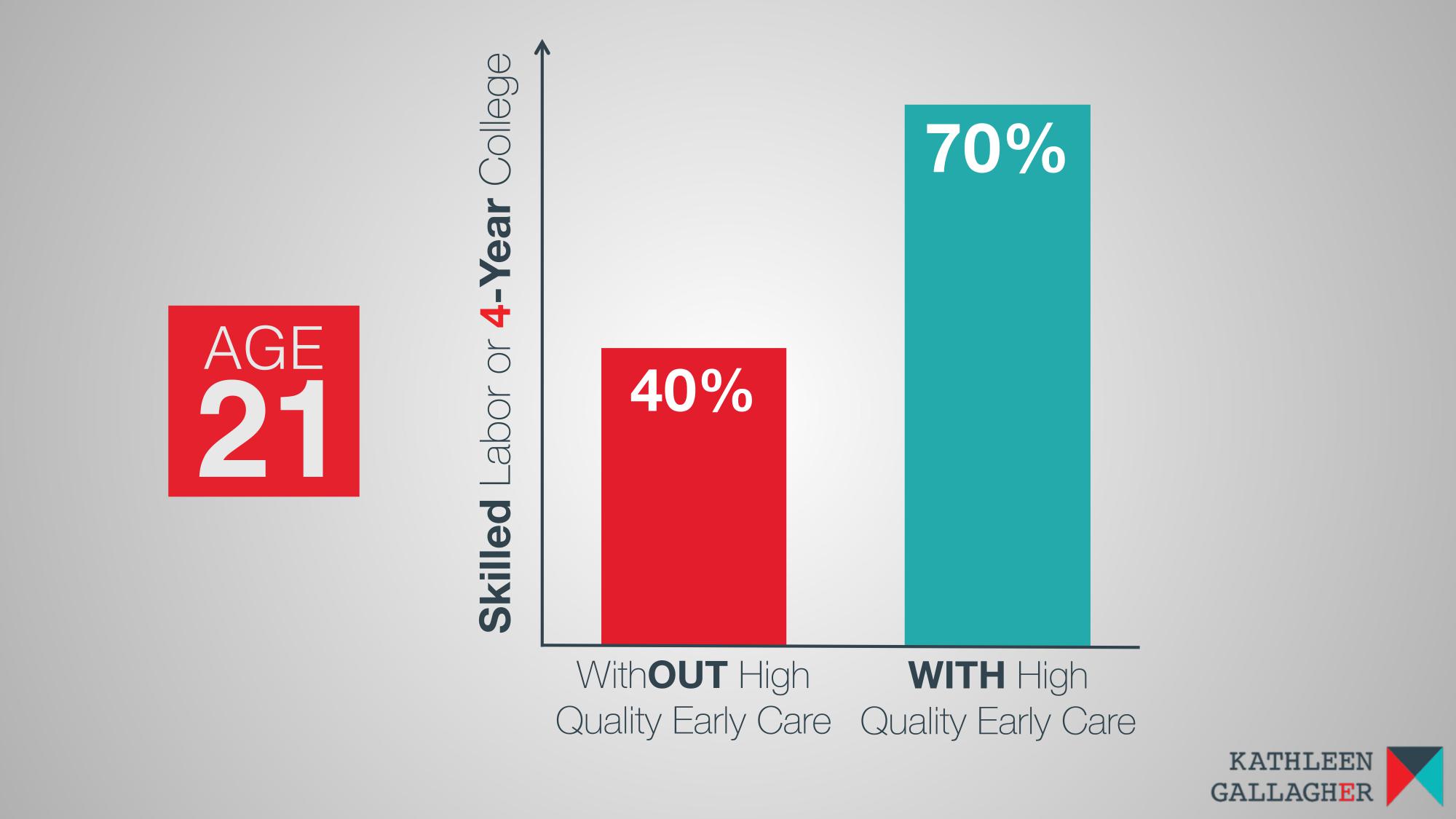

By 21 years of age, only 40% of the non-participants were attending four-year college or employed in skilled labor--compared to almost 70% of the Abecedarians. This is 16 years AFTER their participation in high quality childcare.

By 21 years of age, only 40% of the non-participants were attending four-year college or employed in skilled labor--compared to almost 70% of the Abecedarians. This is 16 years AFTER their participation in high quality childcare.

By age 30, they were more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree and be employed.

And more remarkable than these academic and workforce advantages, as adults the Abecedarians demonstrated health benefits.

They experienced fewer symptoms of depression.

They also had better heart health. For example: at 35 years old, a quarter of the men who did not receive Abecedarian childcare developed metabolic syndrome--a serious medical condition characterized by high blood pressure and obesity. However, of the Abecedarian men, none--not one--of them developed metabolic syndrome.

High-quality childcare--emphasizing language intensive 1:1 interactions with caring adults, experienced in the first five years of life--is associated with benefits for education, employment, and health in adulthood. Quite a story, right?

Now for a sequel to this story. You may have heard of the achievement gap--that children who live in poverty are less likely to be ready for kindergarten, read at grade level, and graduate from high school. That children whose families experience consistent poverty and stress often do not develop the social-emotional skills they need to succeed in school.

Some good news is that states and communities have applied what we have learned from the Abecedarian study, and implemented early childhood programs designed to remediate this achievement gap.

Some good news is that states and communities have applied what we have learned from the Abecedarian study, and implemented early childhood programs designed to remediate this achievement gap.

High-quality preschool programs for 3- and 4-year-olds who live in poverty are one example. Research on North Carolina’s pre-K programs shows that children enrolled for just one year are less likely to need costly special education services, and they perform better on their third grade achievement tests than children not enrolled. Furthermore, while a single year of high-quality preschool has benefits, we know from recent research on childcare beginning in infancy that for children whose families live in poverty, attending high-quality programs at younger ages and staying longer shrinks the achievement gap even more.

How does playing and learning with a teacher at 2 or 4 years old manifest in better health in adulthood? How do these high-quality programs bridge the achievement gap for children whose families live in poverty? We have learned that the programs that produce these types of benefits for children do some special things. They create policies and practices that allow time and energy and space for frequent 1:1 adult child interactions. They require that teachers be well-educated and healthy, and develop strong bonds with children and their families--and high expectations.

The key--that I learned teaching Marcus, and the Abecedarian researchers understood--is that children learn best in the context of healthy relationships. Young children who have healthy relationships with their parents, with teachers and other children, learn that they are worthy of learning and education--of good health and wellbeing. We assemble healthy children by making certain that they have access to healthy, supportive relationships. Healthy relationships literally change the brain structure and prepare it to learn. Literally.

The key--that I learned teaching Marcus, and the Abecedarian researchers understood--is that children learn best in the context of healthy relationships. Young children who have healthy relationships with their parents, with teachers and other children, learn that they are worthy of learning and education--of good health and wellbeing. We assemble healthy children by making certain that they have access to healthy, supportive relationships. Healthy relationships literally change the brain structure and prepare it to learn. Literally.

For early childhood programs, this means providing an environment where children and the adults who care for them have frequent opportunities for 1:1 interactions--from peek-a-boo to following directions to learning the ABC’s. After all, what really worked for Marcus wasn’t just Learning Games--it was his parents and me playing Learning Games all the time. What worked for Marcus was a program that put children and families and their high expectations at the front of everything they were concerned about.

We are missing an incredible opportunity. Our efforts to expand high-quality early childhood programs are important, but thus far our communities have failed to take the right next steps. Only a fraction of young children whose families live in poverty have access to high-quality early childhood programs. We need programs that ensure children’s access to 1:1 intensive interactions--that put relationships at the center of their curriculum--and they can be expensive.

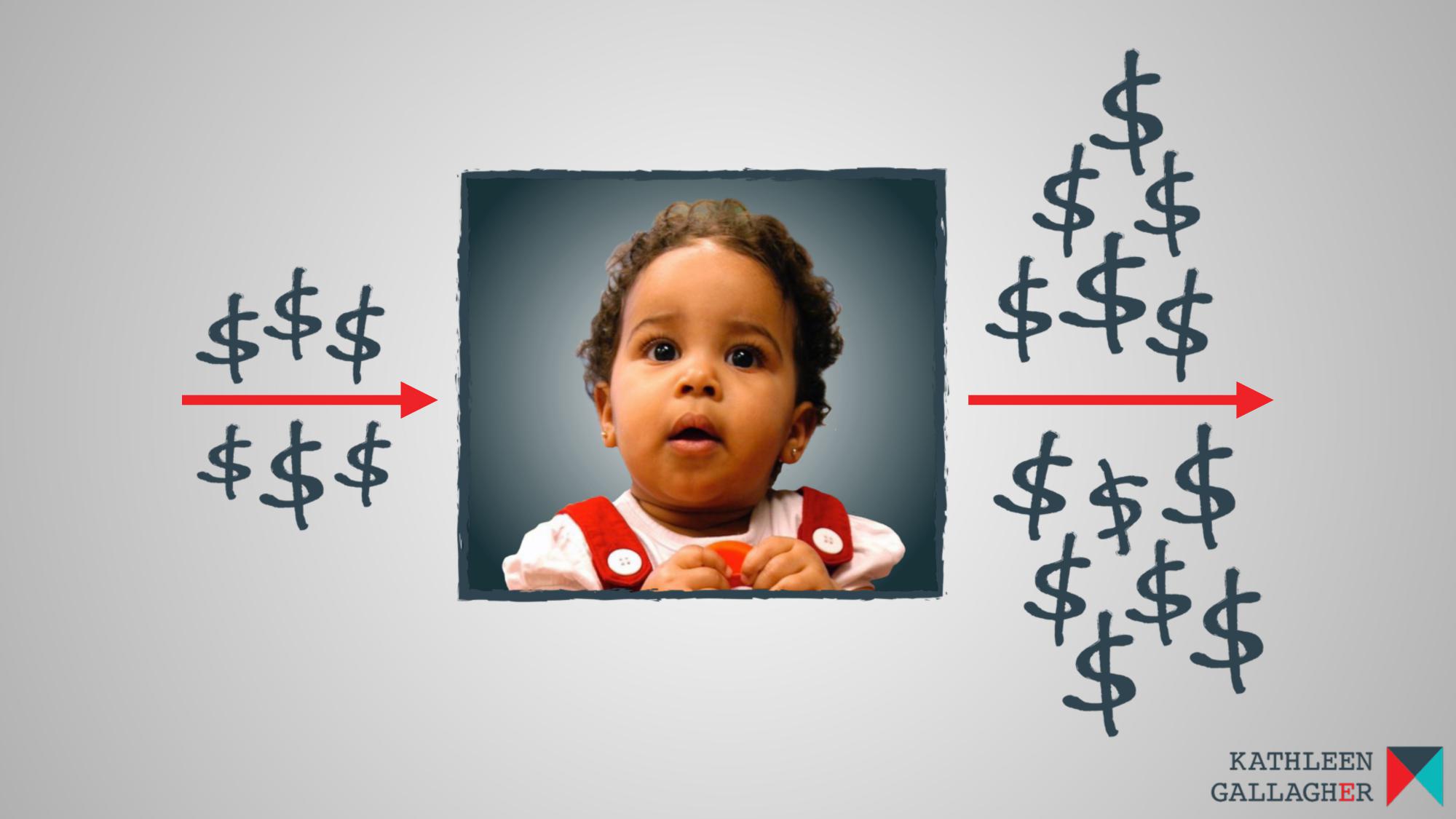

But we have evidence from the Abecedarian project and other studies that high quality early childhood programs offer a substantial financial return on investment. Nobel prize-winning economist James Heckman has shown that people who receive high-quality early childhood care and education save social support programs as much as 7-10 dollars for every dollar spent. And economist Timothy Bartik provides compelling evidence that investment in high-quality early childhood programs elevates the health and wellbeing of entire communities. In fact, Dr. Bartik contends that high-quality early childhood programs could be the most powerful societal support for interrupting the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

But we have evidence from the Abecedarian project and other studies that high quality early childhood programs offer a substantial financial return on investment. Nobel prize-winning economist James Heckman has shown that people who receive high-quality early childhood care and education save social support programs as much as 7-10 dollars for every dollar spent. And economist Timothy Bartik provides compelling evidence that investment in high-quality early childhood programs elevates the health and wellbeing of entire communities. In fact, Dr. Bartik contends that high-quality early childhood programs could be the most powerful societal support for interrupting the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

High-quality early education is about young children and their families, but it isn’t only about them. The benefits--the returns for investing in intensive, relationship-based programs for children--are also about about you, me, everybody. Our neighborhoods, our towns, our communities.

So, who is responsible for taking the “next steps”?

So, who is responsible for taking the “next steps”?

We are.

But if we consistently offer only half of our nation’s children the economic stability to be well, we had better to be ready to intervene. Early. We had better be ready to offer programs, in which educated, healthy teachers are prepared to provide intensive, relationship-based care and education for children, while their parents work and go to school to improve their family circumstances.

What are our next steps? We can start by getting on the phone--letting our local, state, and federal legislators know that providing high-quality, relationship-based early care and education for our youngest children is our highest priority. We can let them know that we will not rest until every child has the resources to support his or her social, emotional, physical, and cognitive health and relationships.

To build economically vibrant communities, we need healthy children to grow into healthy community members who can contribute their resources, voices, informed perspectives, and personal capital. We need individuals whose relationships--in home and community--have taught them what it means to contribute in a democracy. Let’s take those next right steps.