Helping Children of All Abilities: FPG Celebrates 30 Years of Early Intervention and Early Childhood Special Education

On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of landmark legislation for the field, Christina Kasprzak and Joan Danaher explain how FPG’s Trohanis TA Projects have shaped technical assistance and impacted programs that serve young children with disabilities and their families.

FPG's Trohanis Technical Assistance Projects, named for technical assistance pioneer Pat Trohanis, have provided integral support for Early Intervention and Early Childhood Special Education—programs that annually enrich the lives of hundreds of thousands of children with disabilities in every U.S. state and territory.

FPG's Trohanis Technical Assistance Projects, named for technical assistance pioneer Pat Trohanis, have provided integral support for Early Intervention and Early Childhood Special Education—programs that annually enrich the lives of hundreds of thousands of children with disabilities in every U.S. state and territory.

The passage of Public Law 99-457 in 1986 established Part C and mandated Part B: Section 619 of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). These programs have helped to improve child and family outcomes while defending the rights of young children with disabilities and the families of those children. On the occasion of the legislation’s 30th anniversary, FPG’s Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center (ECTA Center) director Christina Kasprzak and associate director Joan Danaher talked about FPG’s role in supporting the implementation of PL 99-457.

The Passage of Public Law 99-457

Joan Danaher: Before he came to FPG, former director Jim Gallagher was an important influence in federal policy for early intervention and early childhood special education, including the first federally funded demonstration projects and technical assistance projects to support them. At FPG, Jim mentored graduate students in policy development and analysis, and FPG also became a locus for national technical assistance projects under the leadership of Pat Trohanis. Barbara Smith, one of Jim’s students who is now at the University of Colorado Denver, was instrumental in developing policy options to expand the early childhood provisions of the law. Working with the Council for Exceptional Children, those ideas were funneled through congressional committee staffers to the legislators who passed the law.

When PL 99-457 was passed, FPG was already positioned to support it after fifteen years of experience providing technical assistance to local and state programs.

Christina Kasprzak: The Trohanis TA Projects have a long history of supporting early intervention and preschool special education—45 years and counting—and Pat Trohanis was an early innovator here at FPG. For many years, he designed and delivered TA that focused on building effective systems and implementing effective practices. He was a brilliant leader. He understood people, and he understood systems. He also had a passion for young children with disabilities and their families. His work supported programs nationally and internationally, bringing recognition and support for systems for young children with disabilities.

Joan Danaher: At the time that PL 99-457 was passed, FPG was supporting states in planning statewide services for birth to school-aged children with disabilities through the OSEP-funded State Technical Assistance Resource Team (START), which Gloria Harbin [left] directed. The new law created the Early Intervention  Program for Infants and Toddlers and added a disincentive for states not to serve all children 3-5 years old with disabilities. Because of these changes to the early childhood programs, OSEP [the federal Office of Special Education Programs] ended the START TA project and issued a call for a new national early childhood TA center that would promote the development of comprehensive, coordinated interagency systems of family-centered services for children birth through age 5. But services for infants and toddlers with disabilities were different from the preschool Special Education program. The governor of a state could assign the lead agency for their Early Intervention program, and some federal requirements meant it was a much different animal from preschool Special Ed. So, it wasn’t easy within states for services for infants and toddlers to synch up with services for preschool-aged children.

Program for Infants and Toddlers and added a disincentive for states not to serve all children 3-5 years old with disabilities. Because of these changes to the early childhood programs, OSEP [the federal Office of Special Education Programs] ended the START TA project and issued a call for a new national early childhood TA center that would promote the development of comprehensive, coordinated interagency systems of family-centered services for children birth through age 5. But services for infants and toddlers with disabilities were different from the preschool Special Education program. The governor of a state could assign the lead agency for their Early Intervention program, and some federal requirements meant it was a much different animal from preschool Special Ed. So, it wasn’t easy within states for services for infants and toddlers to synch up with services for preschool-aged children.

Under Pat Trohanis [right], promoting a new seamless system of services for children birth to age 5—between two agencies for different age groups—became the responsibility of FPG’s new center, the National Early Childhood Technical Assistance System (NECTAS). It was an exciting time for having the opportunity to get early intervention institutionalized, but it was very challenging—and we really had to hit the ground running.

Under Pat Trohanis [right], promoting a new seamless system of services for children birth to age 5—between two agencies for different age groups—became the responsibility of FPG’s new center, the National Early Childhood Technical Assistance System (NECTAS). It was an exciting time for having the opportunity to get early intervention institutionalized, but it was very challenging—and we really had to hit the ground running.

The Legacy of TA at FPG

Joan Danaher: Our technical assistance projects have responded to the evolution of the federal early childhood programs, and we have a perspective on the complete system implementation, starting from local services and demonstration projects and outreach. If you take each aspect of what we have helped clients with over the years—from the Technical Assistance Development System [created in 1971] and START, then, NECTAS and then NECTAC [the National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center, which evolved into the present-day ECTA Center]—some of the same ideas and concepts are refined and enhanced through a spiraling of sophistication, complexity, and an expanding evidence base. The evolution of the TA centers through NECTAC is described in a 2009 article, as is this notion of increasing complexity.1

For example, in the early days, we were doing TA for demonstration projects and helping them document their models in order to replicate them in other places. Today we approach it through implementation science, which gets to that same core of providing a service to the client that is replicated effectively. Services have to be institutionalized, through “systems drivers,” like infrastructure for personnel and finance and governance and all of those aspects that we addressed three decades ago at a much more basic level. Yet, because we have marched down that road in each succeeding generation of projects, we are now seeing the implementation of the law more completely.

Christina Kasprzak [here]: The Trohanis TA Projects have contributed to the field by defining what it means to deliver effective TA. Effective TA is grounded in  social science. It is grounded in the questions What outcomes are we trying to accomplish? and What changes can we make that will result in improvement? Effective TA takes an outcome-orientation based on program evaluation, addressing questions like Which services are producing intended results? Who is benefiting? and Where are improvements needed?

social science. It is grounded in the questions What outcomes are we trying to accomplish? and What changes can we make that will result in improvement? Effective TA takes an outcome-orientation based on program evaluation, addressing questions like Which services are producing intended results? Who is benefiting? and Where are improvements needed?

Effective TA is also grounded in systems change literature, adult learning principles, and shares concepts with improvement science, and, in more recent years, it has incorporated the learnings from implementation science.

From 45 years of TA we also have learned some principles of effective TA. We’ve learned that TA providers must offer a broad range of TA strategies and different levels of intensity in order to effectively respond to the diverse and unique needs of clients. We’ve learned that to be effective, we must build and maintain trusting relationships. Clients must have confidence that their TA providers understand the context of their work, have the content expertise to address their needs, and will provide timely, evidence-based information and resources. Our experience has seen that effective TA requires TA providers and clients to work collaboratively and that successful improvement efforts are built on existing strengths and initiatives. Over the years, we've provided technical assistance to all 60 states and territories—helping them build their systems of service. Our TA projects have supported that evolution from the early stages of establishing a system to serve children with disabilities, to supporting their access to services, and then to focusing on improving the quality of services and outcomes for children and families.

Joan Danaher: We’ve helped write state policies—guidance for practitioners and how children are served—helped with personnel systems issues, and much more. Over time, the evolution from the emphasis on access to services to quality of services to improving outcomes from services means it’s not good enough anymore only to get children in the door. Today, the question is: What kinds of services and how high is the quality and what are the outcomes? This is what has to be the measure of success for the law. Not just getting the kids in the door and providing enough trained professionals—we want to see improved outcomes.

Impacts on Systems, Practices, and Child and Family Outcomes

Impacts on Systems, Practices, and Child and Family Outcomes

Joan Danaher [right]: Over the years, we would always provide OSEP with documents concerning the implementation of the law in states. Those were summary kinds of documents—a look at what's going on—as well as survey information from the states about how and what was happening on that level. For a number of years, we produced annual yearbooks for part C and 619, almanacs that covered a lot of different topics about what the states were doing.

Staff here also participated in writing journal articles and other papers that congressional staff received, and Pat Trohanis provided testimony to congress. All of this would help OSEP and the administration formulate decisions about what changes they needed to address.

Christina Kasprzak: One area where we’ve impacted the field is around the measurement of child outcomes. Prior to 2004, some state Early Intervention and Early Childhood Special Education programs had individualized efforts to measure outcomes. The efforts that existed were disparate. Between 2004 and 2008, the Early Childhood Outcomes [ECO] Center and NECTAC collaborated with federal partners, state administrators, researchers, family members, practitioners and other partners to define outcomes for EI and ECSE, and to assist states in developing systems for measuring these outcomes. Lynne Kahn was director of NECTAC and led our subcontract for the ECO Center, and Kathy Hebbeler was the director of ECO at SRI International. That work led to recommendations to the Office of Special Education Programs, which eventually became requirements for reporting outcomes.

We continued to provide TA through ECO, NECTAC, and now ECTA on collecting, reporting, and using child outcomes data. Today, there is nationally aggregatable data; there is usable data for program improvement efforts. The focus now is to improve data quality and use these data for program improvement. Our annual analysis shows a steady increase in the number of states meeting national criteria for data quality.

Another example of Trohanis TA impacts is summarized in a 2009 publication on long-term systems change.2 The article describes our comprehensive plans with state EI and ECSE programs to improve systems, practices and outcomes. Systems issues included fiscal issues, political turnovers, personnel issues (including staff turnover), and other barriers that states deal with all the time.

Another example of Trohanis TA impacts is summarized in a 2009 publication on long-term systems change.2 The article describes our comprehensive plans with state EI and ECSE programs to improve systems, practices and outcomes. Systems issues included fiscal issues, political turnovers, personnel issues (including staff turnover), and other barriers that states deal with all the time.

At the end of our project, we analyzed 37 state plans to identify impacts on systems, as well as their practice and family-childhood outcomes. All plans showed state system-level impacts. Fifty-one percent of plans demonstrated practice changes, and in 35% we saw an actual change in improved outcomes for children and families. Those numbers increase to 67% and 44% when you take out plans that were not yet fully implemented.

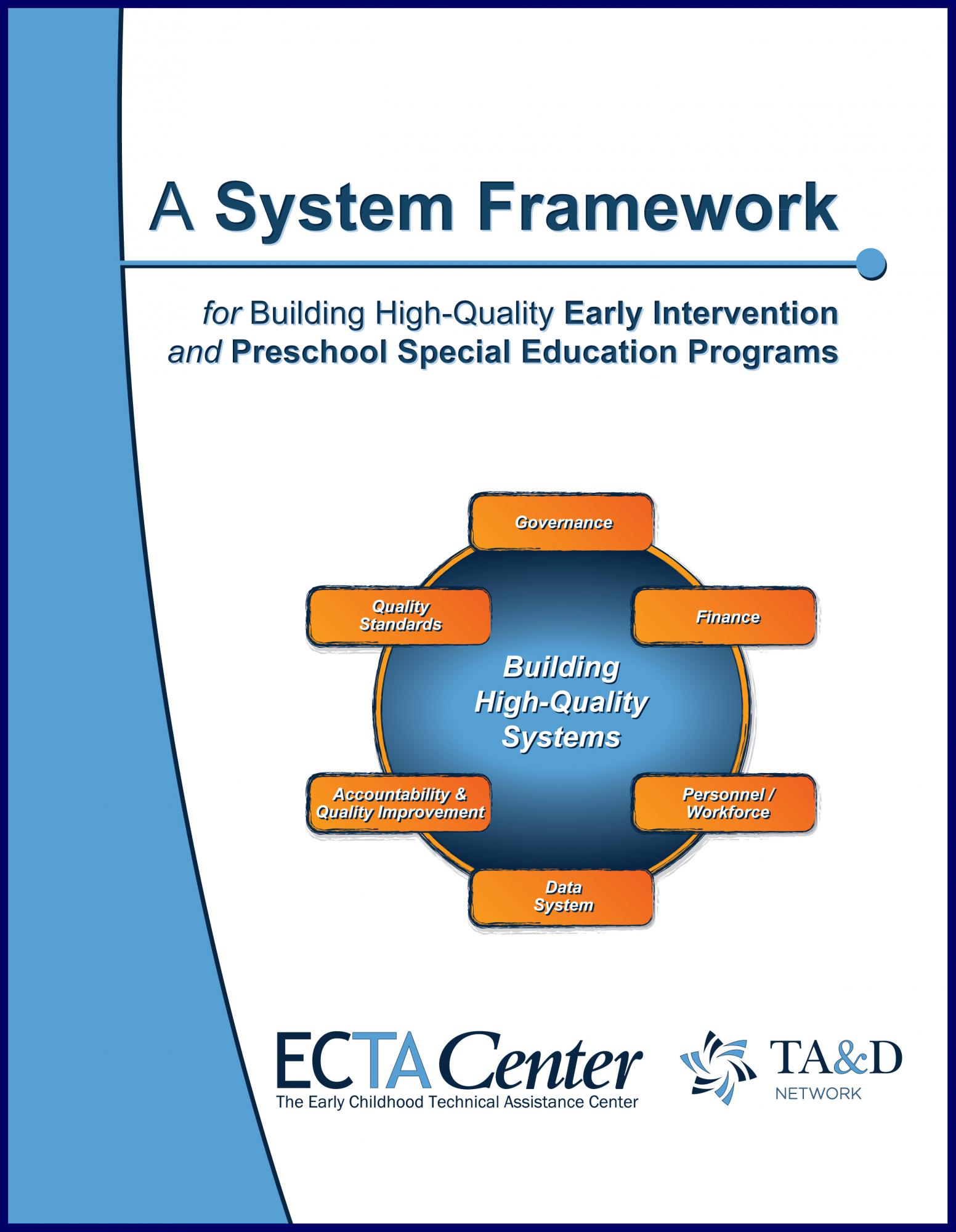

More recently, the ECTA Center has developed a System Framework that describes the components and quality indicators for a high-quality system. It was developed using a 2-year collaborative process, because it was developed with national experts and state partners and was field-tested in states. In a recent national survey, we found that 47 state EI and ECSE programs are using the framework. So we can see widespread efforts around evaluating EI/ECSE systems and planning for improvement using the ECTA System Framework.

Joan Danaher: The ECTA Center has an important focus on practice improvements, which includes supporting the DEC [Division for Early Childhood] Commissioners’ work on Recommended Practices, as well as developing materials that support state and local implementation of the DEC Recommended Practices. Through our cooperative agreement with OSEP, we’ve developed a suite of products for practitioners and families to learn how to apply the DEC Recommended Practices to developmental interventions in everyday routines and settings involving children and families. All of the products and resources are free, including videos starring “aRPy,” an animated spokesperson we created. And we’ve recognized the need to reach practitioners and professional development providers, in addition to state level personnel, with our products. We selected 16 experts across the country to serve as “ambassadors” to spearhead the use of the new recommended practices in their states. We handpicked the ambassadors for their broad expertise and skills. They form a national cohort with knowledge of  evidence-based practices, professional development and training, and their state’s early childhood services and practitioner networks.

evidence-based practices, professional development and training, and their state’s early childhood services and practitioner networks.

Not only will ambassadors collaborate with one another to develop and share strategies and resources, but each will develop and implement goals aligned with a state improvement effort. They’ll also participate in designing, documenting, and making recommendations for subsequent groups as we continue to disseminate materials nationally.

Christina Kasprzak: Although we work with every state, we are working very intensively with four states in implementing and scaling up the DEC Recommended Practices. In that intensive work, we developed and are using a number of tools at the state level with state teams to look at benchmarks of quality, as well as looking in turn at local teams, using local benchmarks of quality. And, at the practice level, we're using observation skills to see what changes are happening in practices and child measures to capture changes at the individual level. In these four states we are documenting changes at the systems, practice, and child outcomes levels, and putting together case studies that illustrate the impacts of our TA.

I’m fortunate to have such a fabulous leadership team. Joan Danaher, Betsy Ayankoya, Megan Vinh, Robin Rooney, and Siobhan Colgan serve as leaders for the Trohanis TA Projects.

Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center

notes

1Gallagher, J. J., Danaher, J. C., & Clifford, R. M. (2009). The evolution of the National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29(1), 7-23. doi:10.1177/0271121408330931

2Kahn, L., Hurth, J., Kasprzak, C. M., Diefendorf, M. J., Goode, S. E., & Ringwalt, S. S. (2009). The National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center model for long-term systems change. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29(1), 24-39. doi:10.1177/0271121409334039