The TED Talk They Keep Talking About: The Power of High-Quality Early Ed

The Healthy Child: Assembly Required

UPDATE: After Kate Gallagher delivered this TED Talk in April, it quickly became UNC's most viewed of the year. You can watch it here. She later delivered the sequel at the TED event in Memphis, and it became that event's most popular talk.

Before a sold-out TEDxUNC conference crowd, FPG's Kathleen (Kate) Gallagher told the amazing story of the children who were part of the most famous study in early childhood—FPG's Abecedarian Project—and she explained the transformative power of high-quality early care and education.

Gallagher extended the theme of the conference, "Assembly Required," to what she called "the single most important feat of construction that our society undertakes...the assembly required to build physically, emotionally, cognitively, and socially healthy children."

The text and many of the illustrations from her talk are available below:

As a senior in college studying early childhood education, I wondered if I should get licensed to teach elementary grades, to increase my employment prospects. My advisor reassured me, “Any day now there will be public early childhood programs everywhere.” Thirty years later, only a fraction of children who most need it, have access to high quality early childhood programs.

This is a story about the single most important feat of construction our society undertakes. It is about the assembly required in order to build physically, emotionally, cognitively, and socially healthy children. It’s a process as complex as the most challenging feat of engineering, and a process that is easily thwarted by poverty and stress. The healthy child does not come pre-assembled: work is required.

![]() This story begins with the amazing journey of 100 North Carolina babies born into poverty, whose life trajectories were altered with a single intervention: high quality educational child care. They remain part of one of the world’s most famous long-running studies of child development—the Abecedarian Project—and it started right here, in this town, at this university, at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute (FPG).

This story begins with the amazing journey of 100 North Carolina babies born into poverty, whose life trajectories were altered with a single intervention: high quality educational child care. They remain part of one of the world’s most famous long-running studies of child development—the Abecedarian Project—and it started right here, in this town, at this university, at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute (FPG).

Abecedarian means “a person who is just learning”–appropriate for its young participants. Since the early 1970s, scientists have followed the Abecedarian children, to investigate how their lives differ from their peers who did not receive the same early care and education.

Here’s how the project worked. Children and families from the Chapel Hill area, who volunteered—and whom all lived in poverty—were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups. Both groups received basic support, such as formula and diapers. But only the children in the Abecedarian group also received year-round, full-time educational childcare.

The innovative Abecedarian program was designed by researchers and implemented by early childhood teachers. It consisted of playful activities, called LearningGames, that emphasized language intensive 1:1 interactions between teachers and children. The researchers expected the fruits of these efforts to be immediately apparent. They had enrolled children as young as 6 weeks old, and started looking soon after for results. But for over a year, they found nothing…

The innovative Abecedarian program was designed by researchers and implemented by early childhood teachers. It consisted of playful activities, called LearningGames, that emphasized language intensive 1:1 interactions between teachers and children. The researchers expected the fruits of these efforts to be immediately apparent. They had enrolled children as young as 6 weeks old, and started looking soon after for results. But for over a year, they found nothing…

Finally, when they were 15 months old, the Abecedarian children began to outperform their peers on cognitive and motor assessments. But no one expected the dramatic long-term effects they would find. First, there were some disadvantages for children who did not receive Abecedarian childcare: non-participating children experienced declines in IQ by their fourth birthday and were more likely to be placed in special education programs in elementary and middle school.

But individuals who experienced Abecedarian childcare outperformed their peers on intellectual measures and reading and math assessments through high school and into adulthood.

Abecedarian childcare participants were less likely to be teen parents.

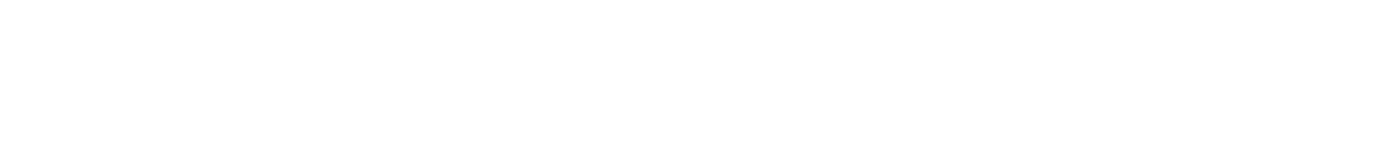

By 21 years of age, only 40% of the non-participants were attending 4 year college or employed in skilled labor—compared to almost 70% of the Abecedarian children. This is 16 years AFTER their participation in high quality childcare.

By 21 years of age, only 40% of the non-participants were attending 4 year college or employed in skilled labor—compared to almost 70% of the Abecedarian children. This is 16 years AFTER their participation in high quality childcare.

As adults, the Abecedarian participants were less likely to experience depression.

By age 30, they were more likely to hold a bachelor’s degree and be employed.

The newest findings have shown even more impressive long-term benefits: by their mid-30s, Abecedarian participants had significantly better physical health than their peers. For example, among the males who had not received Abecedarian childcare, a quarter developed metabolic syndrome—a serious medical condition characterized by high blood pressure and obesity. Guess how many of the Abecedarian males developed the disorder? 25%? 10%?

How about zero? None of the men who had received high quality child care had developed this serious health problem.

High quality childcare–experienced in children’s first five years of life—is associated with better heart health in mid-adulthood. Think about that for a moment.

What made a difference for the Abecedarian children? Why—and how—does high quality early care and education have such a powerful and lasting impact?

What is required for the assembly of a healthy child, who then becomes a healthy adult?

What is required for the assembly of a healthy child, who then becomes a healthy adult?

Researchers at FPG and elsewhere have spent decades investigating and identifying the features of high quality early care and education. We have learned a lot from the Abecedarian study—about things that can make dramatic differences for young children—especially those who live in poverty.

We know that children need healthy environments. The Abecedarian study launched years of work into understanding what constitutes healthy early childhood settings. Tools developed at FPG have been used around the world to evaluate and improve the quality of early childhood programs. However, most children who live in poverty do not have access to high quality environments.

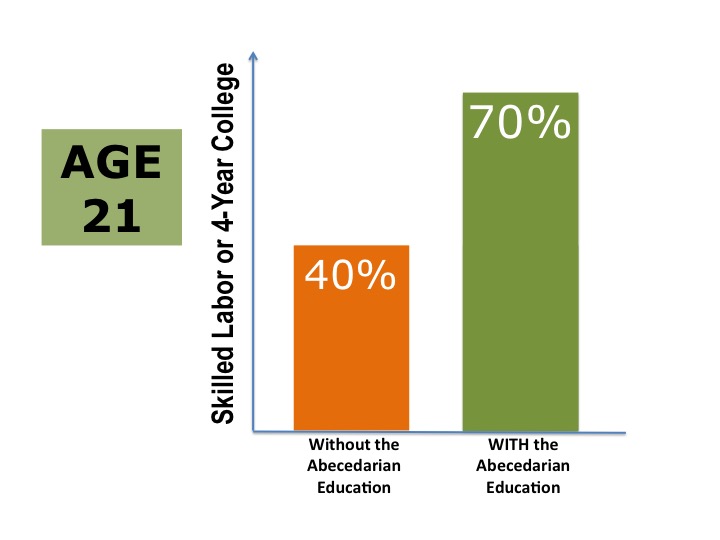

One of the greatest lessons from the Abecedarian study is the importance of frequent, intensive language interactions between adults and children to support healthy development. Research shows that by 4 years old, children who live in poverty hear 30 million fewer words than children growing up in economically privileged homes.

At FPG, we continue to study how teachers in early childhood programs can enhance language development for young children.

At FPG, we continue to study how teachers in early childhood programs can enhance language development for young children.

We’ve established that the glue that holds this assembly together is the presence of warm and trusting relationships forged by the healthy adults in children’s lives. In the Abecedarian study children benefitted from consistent, enjoyable, 1:1 interactions with their teachers. From subsequent research, we know that children who have warm, trusting relationships with teachers in early childhood are more socially healthy and learn better throughout the school years.

High-quality environments, language interactions, and relationships rely on the skills of educated—healthy—teachers. So what do we know about early childhood teachers in this important role?

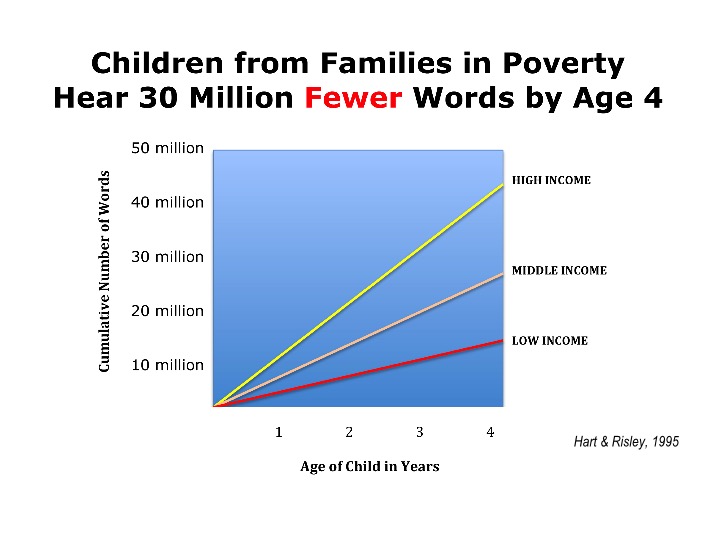

Let’s consider Head Start teachers as an example. Head Start is a federally funded program to educate children whose families are experiencing poverty.

According to a new report on the early childhood workforce, Head Start teachers have increased their education levels consistently since 2007, and yet their salaries have declined in real dollars. Furthermore, research shows that Head Start teachers reported poorer health than the general population, and very high stress in their jobs working with children and families.

And as teachers’ stress increases, the quality of their relationships with children declines.

And as teachers’ stress increases, the quality of their relationships with children declines.

Currently, we are identifying ways to support early childhood teachers well-being, in order to support children’s healthy learning and development.

We are entrusting our future to these dedicated teachers, and failing to provide healthy work environments and a living wage. High quality early childhood education requires healthy teachers.

Healthy environments. Lots of language and warm relationships with educated, healthy, well-compensated, teachers. Sounds expensive, right?

Well, it is.

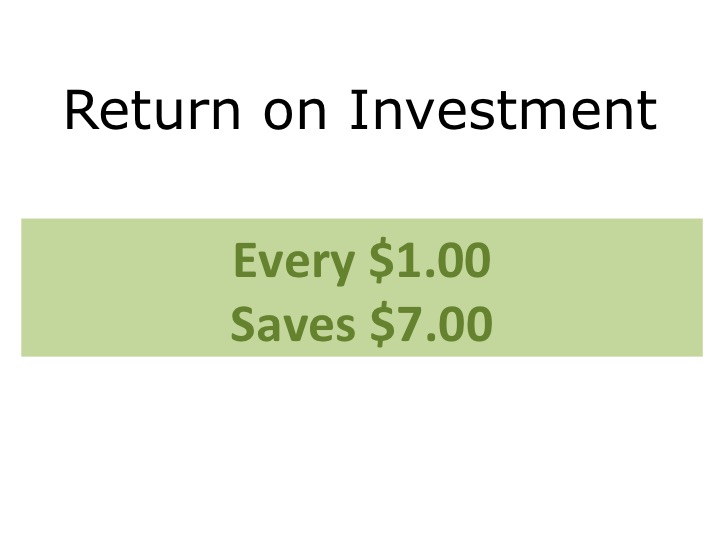

But evidence from the Abecedarian project and other studies demonstrate that there is a financial return on investment as well. According to the Nobel prize-winning economist James Heckman, people who received the Abecedarian early childhood program saved societal support programs as much as $7 for every dollar spent on it.

But evidence from the Abecedarian project and other studies demonstrate that there is a financial return on investment as well. According to the Nobel prize-winning economist James Heckman, people who received the Abecedarian early childhood program saved societal support programs as much as $7 for every dollar spent on it.

And economist Timothy Bartik provides compelling evidence that investment in high quality early childhood programs will not just benefit participating children and families, but entire communities, and could be THE intervention that breaks the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

Do you want to live in an economically stable community, with lower rates of poverty and crime? Invest in high-quality early childhood programs.

Do you want to spend less on public health problems, such as obesity and heart disease? Invest in high-quality early childhood programs.

Do you want your children to benefit from schools where all the children are healthy and prepared to learn? Invest in high-quality early childhood programs.

These days, my office is next door to that of Frances Campbell, one of the original researchers in the Abecedarian Project. But 30 years after my college advisor reassured me, the majority of our young children who live in poverty still don’t receive high-quality early education. Our society’s investment in human capital IS our most pressing and urgent challenge. And if healthier and more productive lives aren’t sufficient proof, we also have a financial bottom line that shows us we must invest early. When children experience poverty and other challenges, we can’t expect healthy development without substantive support.

These days, my office is next door to that of Frances Campbell, one of the original researchers in the Abecedarian Project. But 30 years after my college advisor reassured me, the majority of our young children who live in poverty still don’t receive high-quality early education. Our society’s investment in human capital IS our most pressing and urgent challenge. And if healthier and more productive lives aren’t sufficient proof, we also have a financial bottom line that shows us we must invest early. When children experience poverty and other challenges, we can’t expect healthy development without substantive support.

We have the instructions. Assembly is required.

What are we waiting for?