By: Mary-Russell Roberson

June 1, 2023

A 2023 Preventing Child Trauma Summit Series Article

What are the root causes of trauma in childhood? What are the societal, economic, or other conditions that increase the risk for a child being physically or emotionally abused or neglected; losing a parent to divorce, incarceration, or death; or experiencing discrimination?

It’s a critical question, because child trauma has been shown to lead to adverse effects on multiple domains of development, and these can last a lifetime, including decreased physical and mental health, difficulties forming healthy relationships, poor performance in school and work, involvement with the criminal justice system, and substance use and abuse.

Speakers at a statewide summit on preventing and addressing child trauma spoke about many root causes, including structural racism, historical trauma, discrimination, poverty, lack of affordable housing and nutritious food, lack of healthcare and mental health treatment, community violence, and natural disasters stoked by climate change.

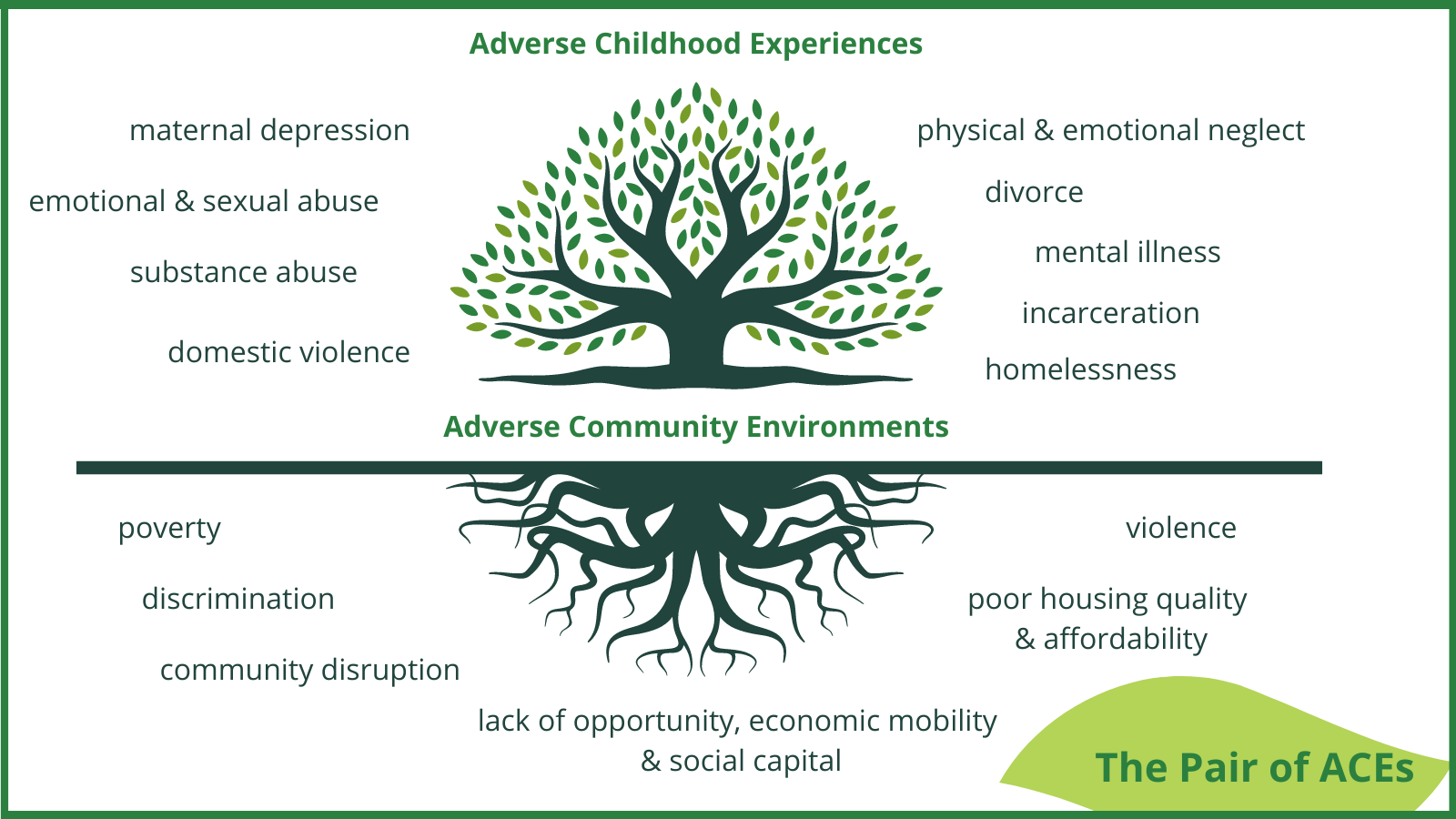

The pair of ACEs tree illustration below demonstrates adverse community environments that underlie the more traditional ACEs.

Racism, Discrimination, Historical Trauma

Speakers presented plenty of evidence showing that adverse childhood events and other types of trauma are more common among children and adolescents who are Black, Latino/a/e/x, Native American, and those who identify as LGBTQ.

“LGBTQ youth are experiencing significant disparities especially around mental health issues,” said Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, MFA, MDiv, founding executive director of the Campaign for Southern Equality. “A primary cause, which research points to and lived experience reinforces, is that LGBTQ youth receive societal, community, and familial messages of condemnation and exclusion at alarming rates and this has a traumatizing impact.” She said LGBTQ students in North Carolina are three times more likely to have thought about suicide or attempted suicide compared to non-LGBTQ peers.

Jada Brooks, PhD, associate professor at the UNC School of Nursing, is an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe and conducts research related to disparities in health and mental health among American Indians. “Compared to the general population, American Indians have lower overall health status and high rates of depression, suicide, anxiety, and substance use,” she said. “Historical or intergenerational trauma undergirds many of the health inequities experienced by American Indians, amplified by the unresolved trauma American Indians have inherited – genocide, boarding schools, forced removal.”

Black and Native American children are much more likely to be involved in the child welfare system than white children. “Black children are 14% of the population, yet 23% of the foster population nationwide, and Native American children have the highest rates of substantiated reports,” said Sharon Hirsh, president and CEO of Prevent Child Abuse North Carolina. “Asking why needs to be at the heart of policy solutions.”

Poverty and Lack of Resources

Hirsh said that one in three Black and Native American children live in poverty, as do one in four Latino/a/e/x children. Among white children, the ratio is one in 11. Families without access to affordable food, housing, and childcare are at high risk for child trauma. For example, parents without access to childcare might have to choose between leaving children alone at home to go to work, or not working enough hours to pay the rent. In the former case, they might be reported for child neglect and in the latter case, the family might become homeless. Either situation is a recipe for child trauma.

The lack of affordable healthcare and mental health treatment, including for substance use, also sets the stage for child trauma. Parents struggle to keep their children safe and healthy when they don’t have the support and resources needed to do so.

When Systems Hurt

When children and families become involved in systems like public welfare, homeless shelters, or the child welfare system, those experiences themselves can be deeply difficult and distressing.

Kim Cook, PhD, professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology at UNCW, said, “These systems produce trauma in and of themselves over and above the [original] trauma.” Cook has personal experience with the welfare system and domestic violence, and has worked with many formerly incarcerated people as part of her involvement with LINC, a program that helps formerly incarcerated people with reentry.

Others with lived experience echoed the sentiment. Kara “Kai” Sanders said the first time she really felt homeless was when she and her son moved into a homeless shelter after months of living in a hotel, in her car, and with relatives.

The child welfare system is particularly fraught, because while children do sometimes need to be removed from dangerous homes, breaking up a family is inherently traumatic, especially if the children involved are very young. “If you have ever witnessed a removal of a child from their parents, it will stay with you for your whole life,” said Aidan Bohlander, PhD, a manager with the National Infant-Toddler Court Program at Zero to Three.

Programs that Help

Presenters shared a number of efforts to decrease child trauma due to root causes and improve the effectiveness of existing systems, including economic supports for families in poverty, Safe Babies Court Team for infants and toddlers in the child welfare system, community programs where people can support each other in healing, Black doulas to reduce infant mortality, Talking Circles to improve mental health in American Indian youth, the Chief Justice’s Task Force on ACEs-Informed Courts, and many more. (Note: These efforts are described more fully in other articles in this series.)

Although some of these programs have been shown to improve disparities, there are no easy solutions for eliminating the root causes themselves. Some, such as racism and other forms of discrimination, are ongoing. As Vernisha Crawford, MS, CEO of Trauma Informed Institute and founder of the BYE Foundation said, “It’s impossible to heal from something you’re still experiencing.”

Nor is it easy to repair the damage from historical atrocities, such as slavery or Native American genocide, whose effects can be passed down generation after generation. Ilana Berman, PhD, adjunct assistant professor in the UNC Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, said that when a traumatized child grows up and has a child of their own, “whether or not the child has been exposed to anything traumatic, you have the impact of trauma on the family unit. That’s how you have the cycle continuing.”

Rodney Trice, PhD, deputy superintendent for teacher & learning, systemic equity, and engagement, Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, sees the effects of this kind of trauma on his students every day. “We can’t ignore the historical racial trauma that underlies a lot of the trauma that our kids and staff and other community members experience,” he said.

While there are no easy answers, presenters and attendees had ideas about how we might move in the right direction as a society.

Steps in the Right Direction

Individuals, coalitions, and society at large have a role to play in addressing root causes. As many speakers noted, it’s a long road. One of the first steps is looking inward. “To practice cultural humility is a lifelong journey, not a thing to check off,” said Angela Tunno, PhD, assistant professor in the Duke Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. “We all have implicit bias. Calling in the impact of structural racism is a lifelong commitment.”

Another important step is building relationships and working with others. Ingrid Cockhren, MEd, CEO of PACEs Connection, advocated doing the work as part of multisector coalitions. “It requires a multisector approach with a focus on collective healing,” she said. “If we want to address issues in present-day society, we have to go through a process that emphasizes the collective. We have to engage in collective liberation.”

Part of that process includes making sure that people with lived experience of the root causes of trauma are involved in the conversation. “Do you have people with lived experience in positions of power and influence?” Cockhren asked. “When you have someone at the table focused on food security, do you have someone who lived in poverty as a child? You have to be able to have everyone at the table so you can provide interventions that are effective because they are driven by people with lived experience and can be clearly aligned with that account of lived experience.”

Cockhren and others touched on the idea of reparations as one way to address historical trauma and present-day structural racism. Iheoma Iruka, PhD, research professor in the UNC Department of Public Policy and the founding director of the Equity Research Action Coalition at FPG, said, “Reparation is a sign that you understand that you have dehumanized a group of people and you are going to publicly repair that damage. We are not healed and reparation is a way to heal and to address the wealth gap that we have because that wealth was stripped. I want us to think beyond the individual. We have collective work to do.”

The UNC Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute's (FPG) FRONTIER program sponsored a statewide summit, “Leveraging North Carolina’s Assets to Prevent Child Trauma,” April 27-28, 2023. Nearly 150 representatives from academia, community and state organizations, lived experience, philanthropy, government agencies, and governing bodies convened in person, and approximately 230 people joined virtually. The summit was organized by Diana “Denni” Fishbein, PhD, director of translational neuro-prevention research at FPG, and Melissa Clepper-Faith, MD, MPH, translational research program and policy coordinator at FPG. This article is one of a series dealing with issues discussed at the summit; find the full series here.